On May 10, 1869, the world’s first live-tweeted ceremonial event took place 80 miles north of Salt Lake City, Utah. Well, almost. The hammer that would drive the last ceremonial spike of the Transcontinental Railroad was wired up to the telegraph machine. The commemorative golden spike was likewise wired. The three blows required to drive the spike into the California laurel tie would register as CLICK CLICK CLICK on the telegraph. Central Pacific Railroad President Leland Stanford raised the hammer, swung, and missed. Instead of a three character tweet, a telegraph operator transmitted a one word message to President Ulysses S. Grant: “done.”

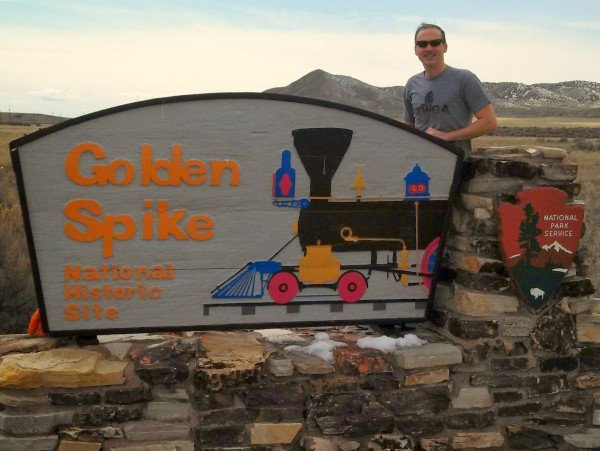

The Monument Marking The Entrance to Golden Spike Historical SiteToday, the 87 mile drive to Golden Spike National Historic Site takes about an hour and a half from Salt Lake City airport. Back in 1869, a trip that far would have easily taken half a day and required anywhere between two and five stops to top off the steam locomotive’s water tanks or take on more fuel in the form of either wood or coal. Cruising along at 60 mph, I almost missed the now-barren railroad grades that once supported the steel tracks of a railroad line. I’m amazed the historical site receives any visitors at all. It’s 28 miles off the main highway, and if it weren’t for the continuous cell phone coverage and occasional ranch house, one could easily get the idea they were in the middle of nowhere.

The Monument Marking The Entrance to Golden Spike Historical SiteToday, the 87 mile drive to Golden Spike National Historic Site takes about an hour and a half from Salt Lake City airport. Back in 1869, a trip that far would have easily taken half a day and required anywhere between two and five stops to top off the steam locomotive’s water tanks or take on more fuel in the form of either wood or coal. Cruising along at 60 mph, I almost missed the now-barren railroad grades that once supported the steel tracks of a railroad line. I’m amazed the historical site receives any visitors at all. It’s 28 miles off the main highway, and if it weren’t for the continuous cell phone coverage and occasional ranch house, one could easily get the idea they were in the middle of nowhere.The sense of excitement on that late spring day must have been intense. Surrounded by barren expanses of land corralled only by not-so-distant mountain ranges, those two sets of connecting tracks represented the gateway to another world. Promontory, Utah was now on the map, a hub of transportation, con artists, and “sporting women.”

Promontory enjoyed a 35 year run as a railroad town on the iron highway to gold and silver country.

Eventually, improved engineering technology allowed for a trestle to be constructed across the Great Salt Lake creating the Lucin Cutoff. The route through Promontory was no longer necessary, and when World War II came along, the rails were recycled for the war effort.

Artifacts from the actual summit are nearly non-existent. A visitor’s center houses a very friendly Park Ranger, a gift shop, and a collection of exhibits describing construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. In front of the visitor’s center is a reconstructed monument—the original is long since deteriorated. Behind the visitor’s center, a benign brass plaque adorns a tie where the final spike was driven. The spike itself was donated to Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, though several replicas are on display inside the visitor’s center. At the turn of the century, train technology was advancing at a speed similar to cell phone technology today. The technology used by the two historic locomotives in the famous picture at Promontory Summit quickly became obsolete. At the turn of the century they were scrapped by their respective owners for about $1,000 each.

Although the original locomotives were scrapped, the crown jewels of the historical site are two replica locomotives built in 1979 by O'Connor Engineering of Costa Mesa, California. As replicas go, these things are Disney-caliber. In fact, Chad O'Connor was a friend of Walt Disney. He was commissioned by the Federal government to build the replica locomotives for $750,000 a piece. He was so passionate about the project that he underbid the job by about half just to make sure he got it (current estimates value the two locomotives at about $3 million each). In the off season (between October and May), visitors can drive across the street from the visitor's center to the roundhouse and get an up close and personal look at the Jupiter and #119.

Ornate Artwork Adorn The Jupiter

Ornate Artwork Adorn The JupiterDuring the summer and early Fall, the two locos are used in daily reenactments of that fateful day in 1869. In the off season, a team of volunteers performs maintenance and reconstruction to keep the machines operating—and looking—as they did in the Victorian Age in which they were born. That means cleaning out boilers, replacing aging brake systems, polishing brass, and repainting the ornate gold-leaf embellishments typical of the era. Walking up next to these things, one immediately notices that they look like they should be in a theme park. The care and attention to detail given to each engine is obvious, and it's hard to imagine investing such artistic attention to detail for such a utilitarian (and dirty) machine. But that's what the Victorian Age was about, and the volunteers working for the Park Service have a passion for maintaining the authenticity of the period. Talking with the mechanics and the Park Ranger, one gains an appreciation of the fact that, perhaps because of this authentic attention to detail, each loco has a personality of its own. That is as it should be, given that neither of the original locomotives they represent were even supposed to be at Promontory Summit back in 1869.

Trains! #trs (@ Golden Spike National Historic Site) http://t.co/oRE0qOWTsQ pic.twitter.com/e1kNpvTX7v

— Sean Genovese (@SLOengineer) March 31, 2014

Leland Stanford had selected a locomotive named “Antelope” to pull his caravan of dignitaries from Sacramento, California to Promontory Summit. The Antelope was closely following another train also enroute to the Summit. The lead train had a green flag mounted on the locomotive, an indication to railroad workers that another train followed closely behind, so keep the tracks clear. Workers clearing out a mountain cut failed to see the flag, and felled a log across the tracks. The Antelope hit the log and was badly damaged. It limped along to the next station where the lead locomotive, Jupiter, had been advised via telegraph to wait. Number 119 With Its Boiler Open For MaintenanceThomas Durant, the Vice-President of the Union Pacific railroad, was also traveling to Promontory Summit with a caravan of dignitaries. As his train reached Piedmont, Wyoming, a crowd of over 400 railroad workers was waiting for him. They hadn’t been paid for three months and forced Durant’s train into a siding and chained it up. Two days later, the men were paid, but the Golden Spike ceremony would now be delayed two days to May 10.

Number 119 With Its Boiler Open For MaintenanceThomas Durant, the Vice-President of the Union Pacific railroad, was also traveling to Promontory Summit with a caravan of dignitaries. As his train reached Piedmont, Wyoming, a crowd of over 400 railroad workers was waiting for him. They hadn’t been paid for three months and forced Durant’s train into a siding and chained it up. Two days later, the men were paid, but the Golden Spike ceremony would now be delayed two days to May 10.The delay caused by the labor dispute gave the Weber River, swollen from heavy rains, time to rise. When Durant’s train arrived at Devil’s Gate Bridge, several supports had been washed away by the raging waters. The locomotive, too heavy to safely cross the bridge, pushed the empty railroad cars across (the passengers opted to walk across, fearing that even the cars would be too heavy for the weakened structure). Luckily, five more locomotives were sitting in a Union Pacific rail yard in Ogden. Closest to the main line was number 119. She picked up Durant’s stranded train cars and pulled them to Promontory Summit, just in time for a ceremony now two days late. The Tender of Number 119

The Tender of Number 119

The Tender of Number 119

The Tender of Number 119It wasn't the site of the first "live-tweeted" event. It's claim to fame was short-lived. It isn't heavily trafficked or extravagant. It isn't even a landmark. But Golden Spike Historical Site honors a milestone in American History. If you're in the area, stop by and tweet for yourself.